The deep anatomy of last year's devastating quake in Nepal is revealed in a new analysis by scientists.

Satellite data is used to show where and how the rocks ruptured under the country, leading to the loss of more 8,800 lives.

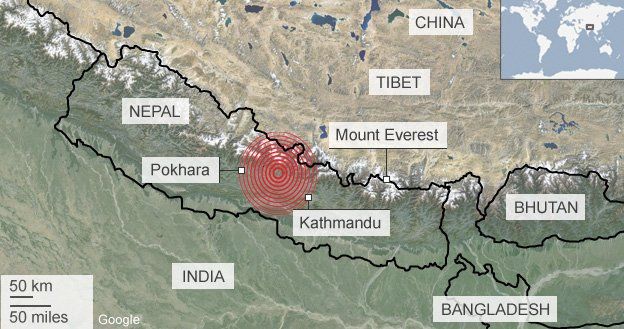

The Magnitude 7.8 tremor occurred at a point where the main fault takes a deep dip just south of the high Himalayas.

This "ramp" structure, as the group calls it, probably also plays a key role in building the famous peaks.

As tectonic forces drive the Indian subcontinent under Central Asia, rocks ride up the ramp, adding a few millimetres a year to the height of the snow and ice-capped mountains.

AFP

AFP

John Elliott from Oxford University, UK, and colleagues report their assessment of the 25 April quake in the journal Nature Geoscience.

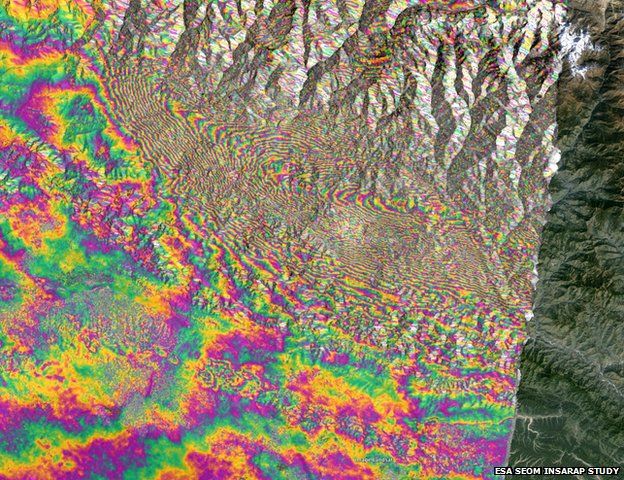

They examined images from Europe's Sentinel-1a radar satellite and other spacecraft to map the buckling of the ground.

These pictures enabled the team to infer what was going on deep beneath the surface.

ESA

ESA

The researchers trace the quake activity to a locality some 10-15km down.

It was spread across what they term a "hinge point", where the main fault in the region transitions from being relatively horizontal to being sharply angled into the Earth.

This geometry has a number of consequences, the scientists say.

First, it neatly explains why the surface surrounding the capital Kathmandu rose up by about a metre during the quake, and dropped by roughly 60cm in the more mountainous terrain to the north.

And, secondly, it also provides a good model for how the Himalayas gain height over time.

The team proposes a cycle of slumping on the occasion of major quakes and mountain-building in quiescent periods, with the increase in elevation dominating over the long term. The high Himalayas currently gain on average about 4mm per annum.

Last April's tremor occurred in what scientists refer to as a seismic gap - a segment of the fault that has not experienced any significant strain-releasing activity in a long while.

The 2015 shock brought relief only to the far eastern sector of this gap, meaning the potential for future large quakes is still present to the west.

And there is potential also to the south.

The latest analysis demonstrates that the main fault did not rupture all the way to the surface on 25 April. It stopped abruptly some 11km under Kathmandu.

"There is still half of the fault - that's going south of Kathmandu, from a depth of 11km up to the surface - that hasn't yet broken," Dr Elliott told BBC News.

"Our hypothesis is that the abrupt stop is because the main fault has been damaged and it was held up where it intersected with other, smaller faults. But this will only be temporary.

"These earthquakes tend to happen on the century timescale, but this barrier could be pushed through on a shorter timescale. Of course, our problem is that we are not able to predict when; we can never give a date."

The Oxford scientist said that if the remaining portion did break all the way to the surface in one go, it would likely produce a quake of similar magnitude to the 25 April event, but being much shallower could have more damaging effects.

How Europe's Sentinel radar satellite viewed the Nepal quake

ESA SEOM InSARap Study

ESA SEOM InSARap Study- S-1a practises something called Synthetic Aperture Radar Interferometry

- This finds differences in "before" and "after" radar pictures taken from orbit

- It enables quake scientists to detect even quite subtle ground movements

- The amount of deformation is depicted in coloured contours, or "fringes"

- Each contour shows 2.8cm of ground movement with respect to S-1a

- 34 fringes in this image equate to a peak ground deformation of about 1m

- The quake ruptured east from its epicentre; the fault did not break the surface

No comments:

Post a Comment